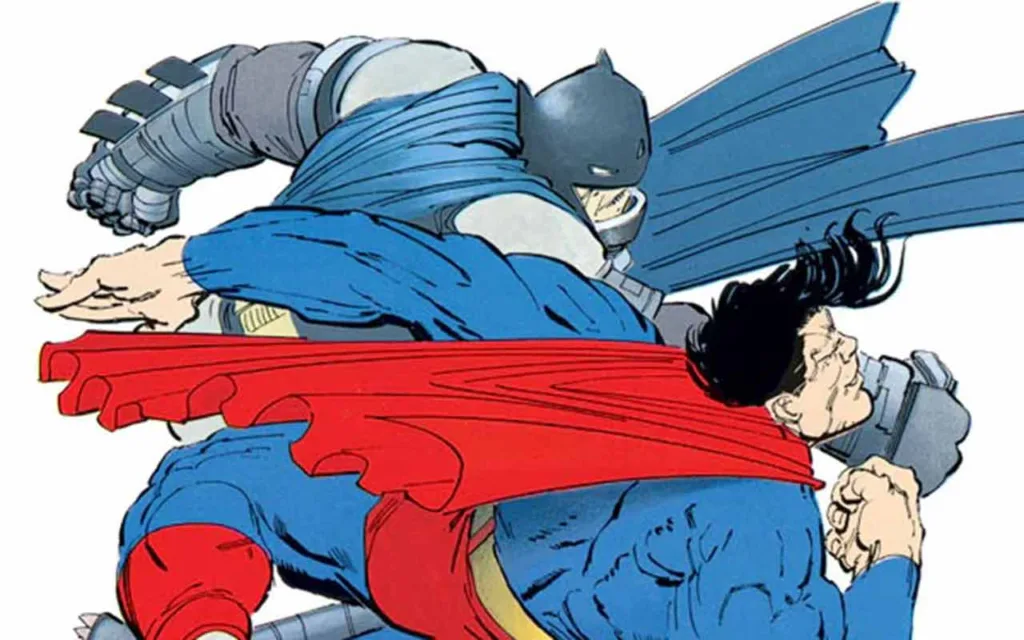

Ask a typical Batman fan for their top 5 Batman stories, and odds are good that at least one of them will be Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns.

While it successfully redefined the character for a new generation, Miller’s cynical, hard-bitten, and violent Dark Knight is responsible for the final demise of the Golden/Silver Age version: The World’s Greatest Detective.

Heroic Legacy of “The Masked Playboy”

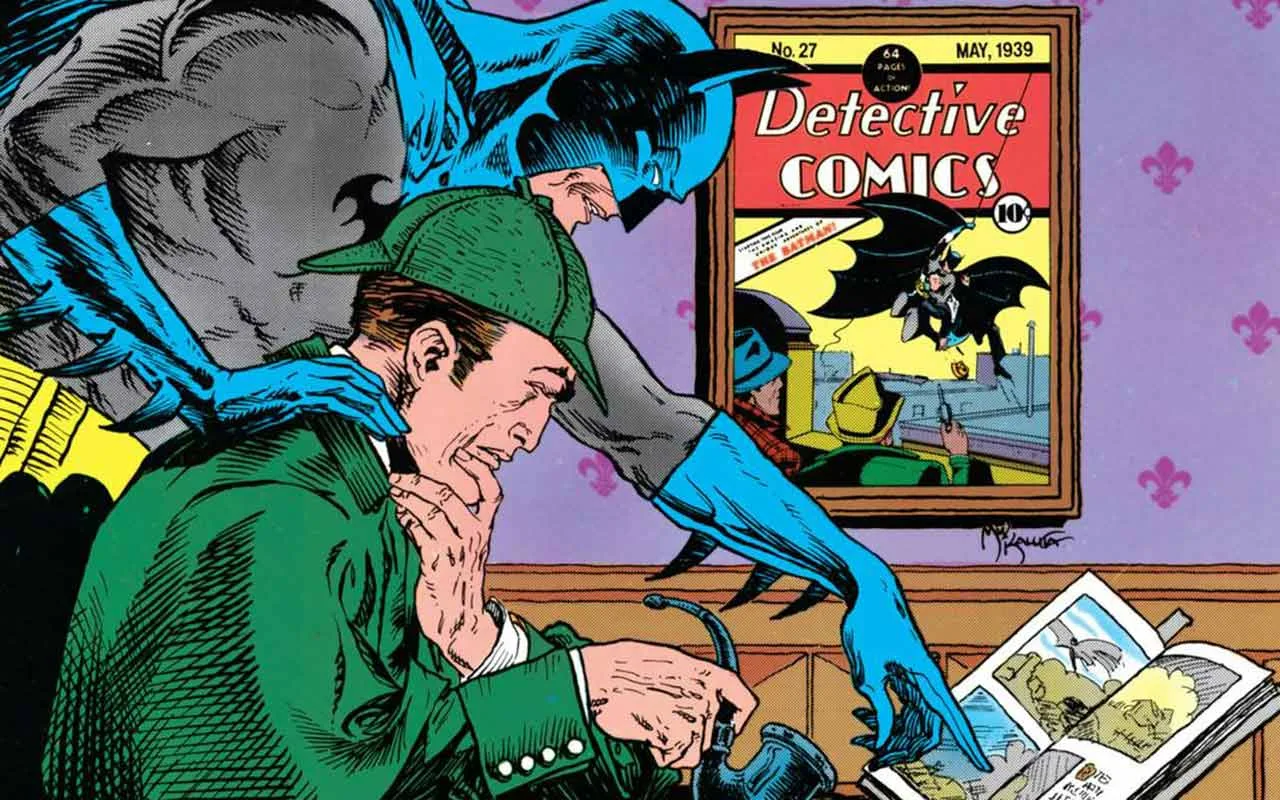

Beginning with Kane and Finger’s original version of the character in 1939, Batman exists as the modern iteration of the long literary tradition of the class-traitor noble who uses their assets to defend the disadvantaged. Miller’s version eschews this heroic tradition and recasts Batman as a sociopathic loner. Key to the original model is the (albeit problematic in another way) idea that the traitorous noble uses their wealth to acquire knowledge and understanding beyond that available to the masses, and then deploys that knowledge on their behalf.

Like Sir Robin of Loxley (Robin Hood) or Sir Percy Blakeney (The Scarlet Pimpernel), the Golden Age version of Bruce Wayne rejects the expectations of his noble social class to focus his deep pockets on protecting the vulnerable people of Gotham. This aspiration model of the character asks that the best of the elite classes seek to build their legacy through anonymous good deeds rather than self-promotion or self-enrichment. It is a social compact that expects more than self-interest out of a city’s “knight.”

Batman inherited this mantle from the likes of 20th-century pulp and radio heroes like The Shadow and Doc Savage, who also employed the “westerner-with-resources-learns-kung-fu/science” trope to great effect. It is an old-world plot point remaining from the age of heraldry and the Crusades, revamped for America’s capitalistic aristocracy. In this model, Bruce Wayne’s tragic loss leads him to master his mind, body, and spirit through years of study and travel, and then joyously serve as his city’s protector.

It was this version of Batman who gave rise to radio shows of his own, serials in the movie theaters, Saturday morning cartoons, generations of stories, including the masterworks of Jim Aparo and Denny O’Neill, and even the campy Adam West Batman TV series. He was universally acknowledged as one of the greatest heroes of his era, a co-founder and leader of the Justice League, and every kid in the world wanted to be his sidekick, Robin.

Miller showed us was what happens when he fails, and it became the standard.

From Detective, To Dirty Harry

The 1980s saw a profound shift in American cultural tastes from previous decades. Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone sold retribution, carnage, and testosterone with every movie ticket. Toughness meant punching harder than the other guy, and sympathy was for sissies.

In the wake of the Adam West Batman series, and the subsequent made-for-TV films, DC was eager to shift audience perception away from the silly, “what do you do with a bomb?” version of the Caped Crusader. In 1986, a year whose films included the war-friendly box office hits Top Gun, Platoon, and Aliens, Frank Miller’s Batman knew exactly what to do with bombs. He strapped them to the roof of his diesel-powered, super-sized Bat-Tank and fired them straight at the hordes of inhuman monsters who’d made him feel bad about America. It was a new day in Ronald Reagan’s U-S-of-A, and Batman was back as an old American aristocrat, to remind you to speak to your elders with respect and stop wearing weird clothes.

At its core, The Dark Knight Returns is a story about what happens to a man who pursues a noble goal, fails, and then cannot live with his own failure. He has alienated every ally he ever had. The only person who understands him is his nemesis. His answer is to double down, fight his best friend in a death-match, fake his own death, and go into hiding. It’s the ultimate “get off my lawn or I’ll take my ball and go home” temper tantrum from a bitter member of the Baby Boomer generation.

Taken by itself, it’s a stirring and emotionally charged portrait of a Batman at the end of his life, trying to correct his mistakes. But the consequences of its success in the mainstream of popular culture would lead to future DC editorial regimes deciding, over and over, to make this version of Batman THE version of Batman. He knows he’s not okay and revels in it, a feature that would find its way into Tim Burton’s take on the character, cementing it in the minds of a new generation, telling them, “You want to get nuts? LET’S GET NUTS!” Jeph Loeb’s Batman in Batman/Superman knows that he is “fundamentally not a good person,” and Zack Snyder’s Bruce knows that he and Alfred have “always been criminals.”

Miller’s Reagan-esque take became the blueprint for new iterations moving forward, costing the character his place as an aspirational figure. For lifelong fans like Kevin Smith (filmmaker and host of the podcast formerly known as Fat Man on Batman), the visceral, grim, and violent aesthetic resonated with them in a way that felt mature, validating their love of the character. For fans of the version which predated Miller, however, he and the success of his embittered, surgically ultraviolent lone wolf led to the wholesale elimination of the World’s Greatest Detective they had loved.

Batman becomes a lone wolf instead of a community builder and leader. He stands apart from what Miller sees as decaying institutions. The Gotham PD are his enemies (other than Commissioner Gordon) rather than his allies. Among the Justice League, he is the human outsider in a room full of gods, rather than the moral compass of the world’s greatest heroes. It is so radical a departure from his behavior immediately pre-TDKR that later writers like Brad Meltzer would attempt to explain the almost psychotic break as the result of the Justice League tampering with Bruce’s mind in the event series Identity Crisis.

The idea of the Dark Knight being a noble has been completely abandoned. Batman replaces the underprivileged, orphaned Robin from the streets (Jason Todd) with a child of privilege from a healthy home (Tim Drake). He abandons Wayne Manor, the Batcave, and all the trappings of his pre-crisis lore for the Wayne Foundation Tower. He replaces Alfred, the quintessential gentleman’s gentleman, with Harold, a barely verbal autistic man whom he employs to make all his toys.

Miller’s Batman fights not for Gotham or for his friends and family, but to satiate a deeper, violent compulsion. Crime is what hurt him, and his power is used for vengeance, not justice.

Whatever happened to the World’s Greatest Detective? He was eclipsed by the Dark Knight of Reagan’s America. And that shadow lingers to this day.

Comic Book Club Live Info:

Discover more from Comic Book Club

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.