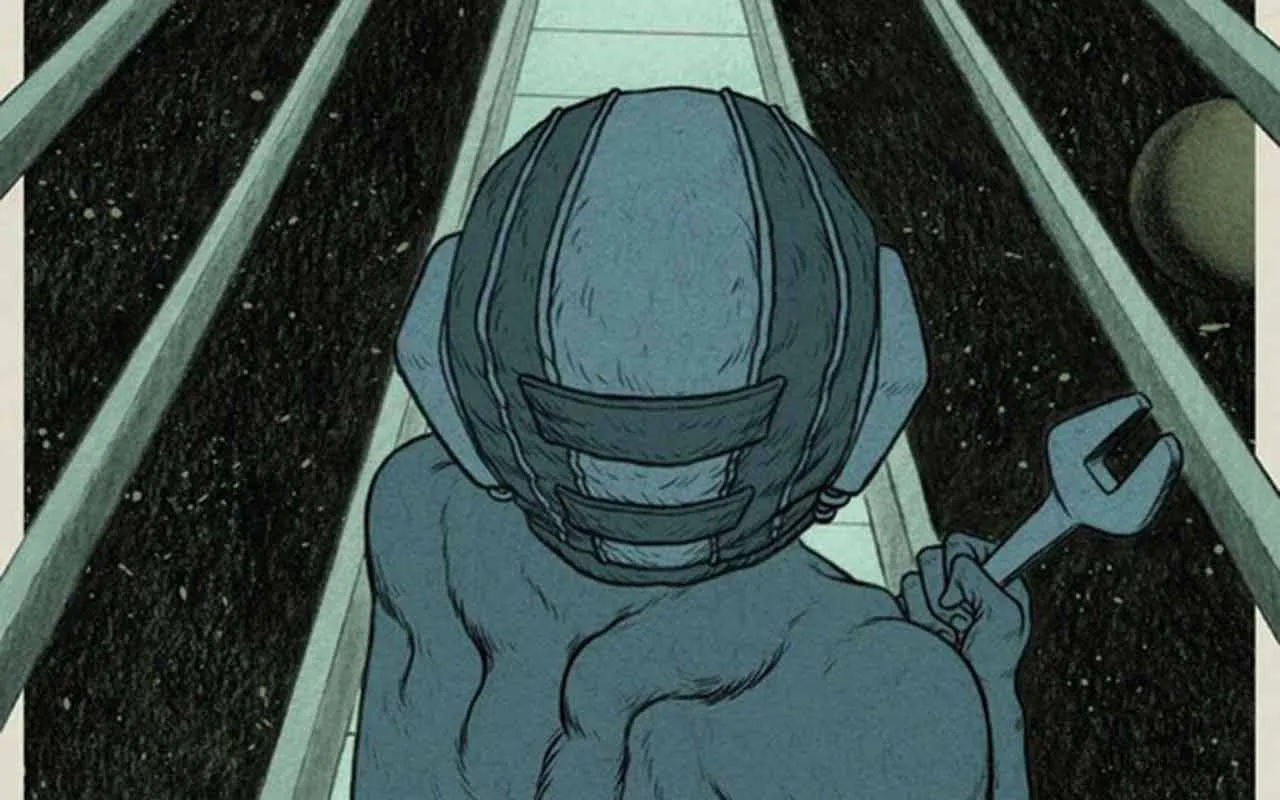

Last week (April 8), Oni Press released Station Grand, a haunting new graphic novella by Craig Hurd-McKenney and Noah Bailey. In it, an astronaut is lightyears from Earth, dealing with insomnia, and maybe an alien presence. It’s a gorgeously written and illustrated book that has a lot more on its mind than “space adventure” — as Hurd-McKenney explained to Comic Book Club.

“It’s not so much space, but what it takes to explore space that fascinates me,” Hurd-McKenney said in an email interview. “Space exploration is not for the weak of spirit. The math and science of it all, the level of genius, as well as the level of bias and exclusion, is staggering. But it’s also the level of disconnect the individuals must have in order to face the extreme danger of it, in putting their lives on the line for increasing our knowledge and understanding of the universe.”

In the book — and spoilers/trigger warning for sexual assault past this point — it becomes clear that at least part of Dr. Michael Kinney’s experience has to do with him being molested by a priest when he was young. And through mixed media and various storytelling approaches, the team explores what this means in both space and on Earth. To find out more about Hurd-McKenney’s approach to the material, read on.

Comic Book Club: You talk about your own troubles sleeping towards the end of the book, but where did the idea come from to move this into space?

Craig Hurd-McKenney: I’ve always been obsessed with outer space. I wanted to be an astronaut when I was a kid, and visiting both NASA and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum were brain-altering experiences for a young farm kid from a working-class background. However, I absolutely draw the line at freeze dried ice cream!

I was also in a full-on insomnia run, meaning that it had been about a week of no sleep, so I was reading a lot about possible treatments, other people’s insomnia narratives. And I came across a lot of articles about insomnia in astronauts. It was too fascinating to let it go, and the rest is history, is in your hands now as Station Grand.

In general, what is it that fascinates you about space?

It’s not so much space, but what it takes to explore space that fascinates me. Space exploration is not for the weak of spirit. The math and science of it all, the level of genius, as well as the level of bias and exclusion, is staggering. But it’s also the level of disconnect the individuals must have in order to face the extreme danger of it, in putting their lives on the line for increasing our knowledge and understanding of the universe. I was in middle school and watched the Challenger explode on live tv. It was in that moment that my naïve love for space and the intense adult world of space collided. I am not an astronaut, so we could possibly assume I am not mentally or spiritually strong enough for space. But this internal struggle, that is what gets me. Ultimately, I’m obsessed with the gamut of stories we have about such explorers, from Fantastic Four to Hidden Figures. And now, here we are, talking about Station Grand.

Perhaps this is the point of exploring lucid dreaming, but how much should we take as lightly veiled truth versus fiction?

From a creative perspective, I’d say that you should always take lucid dreams as the truth. They can really provide a doorway into your story. I’m a huge David Lynch fan, and he talks a lot about dreams and the unconscious, and channeling those into your creative work. Meditation was a way for him to unlock such things. For me, it’s sleep deprivation and hallucination (I recommend meditation). But it was in Twin Peaks: The Return that he gives the lines to Monica Bellucci: “We are like the dreamer, who dreams and then lives inside the dream. But who is the dreamer?” So practically speaking, we are all the dreamers living in a dreamlike state. It is through our consciousness that we experience the world, or the dream. When we apply that to Station Grand and Dr. Kinney, there might be an urge to read what is happening as hallucination, as fiction. But I suspect that some people will see it as a literal telling of events. That subjective experience of the book is what I’m very excited about, and it is my hope that people will explore both the truth and the fiction of it. I’ll just complicate this by asking: is Dr. Kinney a reliable narrator of events?

It becomes clear early on that you’re suggesting that our main character was molested by a priest, but I was surprised by the matter-of-fact way that info is confirmed by the ship’s computer… What led to the choice to present that crucial piece of info this way?

Our editor, Gabe Granillo, smartly asked us to create a new intro that provided some more information on Dr. Kinney, who he is before we see him on Station Grand. As Noah Bailey, the artist, and I talked about who we saw Dr. Kinney as, we settled on an isolation on Earth that would be reflected in his life in space. The things that were meant to keep him safe, like his parents, like religion, have failed him. Science is safe, it’s reliable. So he has pulled himself into that world for self-preservation. There is a part of him that wants to hold onto the past, reflected in his packing the childhood book in his suitcase. No one wants to feel alone or give up on these deep relationships, even though sometimes that would be best. So all he has on Station Grand is the computer. In some way, the bluntness of the computer addressing its concerns with Dr. Kinney over the issues of his mental health and victimization heightens his lack of social connection. But it is also on some level meant to be startling. Imagine your Switch or your iPad talking to you like that. It might make us all more mentally healthy and accountable. But, to me, there’s also something very sinister about it. Can I trust that this thing is telling me the truth, or is it forcing an outcome that it wants? Who programmed it? What information has it been fed? So you start to see the problem of the computer from Dr. Kinney’s perspective.

Another theme you’re exploring here is isolation which, I imagine, as a comic creator, is a good chunk of your life. How much of this book is wrestling with that feeling?

All of it, and then some. I am very lucky to mostly work with artists I deeply know and like, and can call friends. We probably talk a lot more about the work than maybe in some other creative relationships. But when I first started making comics, it was a definite vacuum as I had not built these friendships over time. So I’d write and write and write, and then send to an artist I didn’t know very well, who maybe wasn’t sure how to ask questions or make suggestions for fear of being irritating or bossy or whatever. And then I awaited the results. I never had a bad experience, but I love the connection with the people with whom I work. Noah likes to surprise with his pages, so he asks for some room to find his way into the story. Another collaborator, Jok (In Hell We Fight from Image Comics, The Body Trade from Mad Cave Studios), has a big comfort level with me, so we will go all in on staging a scene if he feels it isn’t working. I trust both of them implicitly, and we all just want the book to be amazing. The takeaway is that creating comics is less isolating than it used to be.

That said, I still wrestle with it in other areas of life. As I’ve aged, my social circle has gotten smaller. People get caught up in raising their kids, caretaking aging parents, or just disassociating given the state of the world. I feel the isolation creeping in at the edges there, but it hasn’t taken over fully. It’s just part of being alive that your social connections will ebb and flow, and you can respond like Dr. Kinney and fly away to Venus, or you can hunker down and try to build new connections.

There are multiple art styles employed throughout here… What led to those choices, including mixed media in the back story?

Oh, that’s all thanks to the brilliant Noah. As I said, Noah likes to surprise with pages. I give him the space to do his magic, and then wait for the pages to come in. Noah loves to try new materials, new approaches, and I fully support that. We talked about collaboration and connection, and I want people to feel like the work is worth the time they are going to spend on it. So the best I can do is get out of the way of the experts and let them do their thing. And in this case, Noah did just that. There is one page I still gasp over. It’s about halfway through the book, and Dr. Kinney is on his tablet, eating a meal. It’s six ostensibly simple panels, but the way Noah has juxtaposed the outward and inward worlds, is absolutely, mind-blowingly emotionally evocative. I’d also recommend watching carefully in the backgrounds as the book progresses. Noah’s doing some deep storytelling there.

Rather than what you want the reader to take away from Station Grand… What did you take away?

I love this question. I don’t want to influence the way anyone reads the book, so I’ll answer very carefully here. I know what I took away is partial catharsis of some of my own struggles. For instance, I’ve now heard from other people who also suffer from insomnia, and it all feels a little less lonely now.

I also get to talk to other people like you about the work, and that is a deeply meaningful part of the process.

And I have this amazing bond with Noah, Gabe and Saida Temofonte, our letterer, now.

Station Grand is available in stores now.

Comic Book Club Live Info:

Discover more from Comic Book Club

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.